Brandenburg Concertos Nos. 2 & 4

By John Lenti

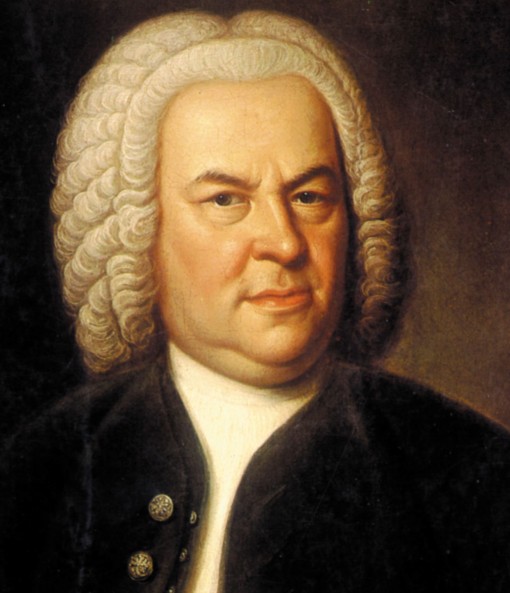

J.S. BachBach’s Brandenburg concertos were submitted as a job application in 1721. Comprising six concertos of entirely different instrumentation, they didn’t impress the Margrave of Brandenburg, whose orchestra didn’t have enough members to play them anyway, and these glorious pieces languished in his archives until 1849. Since their publication the following year they’ve remained popular, and one of them will outlast humanity, hurtling through the cosmos on the Golden Records on the Voyager probes.

Lucky aliens of eons hence! With trumpet, recorder, oboe, and violin soloists with string orchestra and continuo, Brandenburg No. 2 is a fun study in baroque virtuosity. There’s something mystical in the ability to negotiate the clarino trumpet line without valves, particularly in a range for which any modern trumpeter would simply say, “give me my smallest trumpet.” With the advent of valved trumpets and the extinction of clarino technique in the eighteenth century, the piece was practically unplayable until the revival of the natural trumpet with the early music movement, and even now, it’s a fearsome beast.

The material of the first movement is laid out in its first few seconds: two themes, the martial trumpet theme, and then the lyric countermelody in the violin solo, are shared among all four soloists, showing Bach the Vivaldian using very simple material to build excitement. In the middle movement, the orchestra and the trumpet sit out while the other soloists dovetail in a lengthy meditation on the appoggiatura. This beautiful Italian word means “leaning,” and it refers to holding a note just a little to produce tension, before relaxing onto the note below, generally with a stress pattern something like the name “David.” The final movement is a straightforward fugue with accompaniment which happens to be the most exciting trumpet solo ever written.

The fourth Brandenburg concerto, with two recorders and violin accompanied by strings, shows us Bach’s mastery of textural variation. While much of the musical interest in the first movement is concentrated in the recorders, the violin comes on strong with some bristling filigree. Bach changes registration in the second movement as the three soloists become a trio alternating with the orchestra, the violin relegated to an accompanimental role as the recorders take turns with the pulsating theme. The fugal third movement begins with the violas (their big break!) with the recorders playing in unison at times, but then clearly delineated in soloist passages. Again, the solo violin soars out of the fray, this time with a lengthy passage in bariolage which, at any reasonable tempo, is scary.

—John Lenti

*look Bach’s arrangements up later: RV580 became the 4-harpsichord concerto BWV1065, RV565 and 522 became organ solos, BWV596 and 593