Nate Helgeson: Auld Lang Syne

If you get regular emails from PBO you probably saw the little Auld Lang Syne video we put out on New Year’s Eve. (If not, watch here or below)

If you did, you may have noticed some small differences in the tune from what you’re used to (if not, that’s ok, they’re subtle). Intoxicated New Year’s revelers today vary in the exact notes we tend to sing, but typically there are more deviations from the pentatonic scale common to many folk musics (if you sing two different notes for the first ‘Old’ and the ‘a’ in the first ‘acquaintance,’ that’d be one example of a non-pentatonic change) and the characteristic “Scotch snap” rhythm is often ironed out.

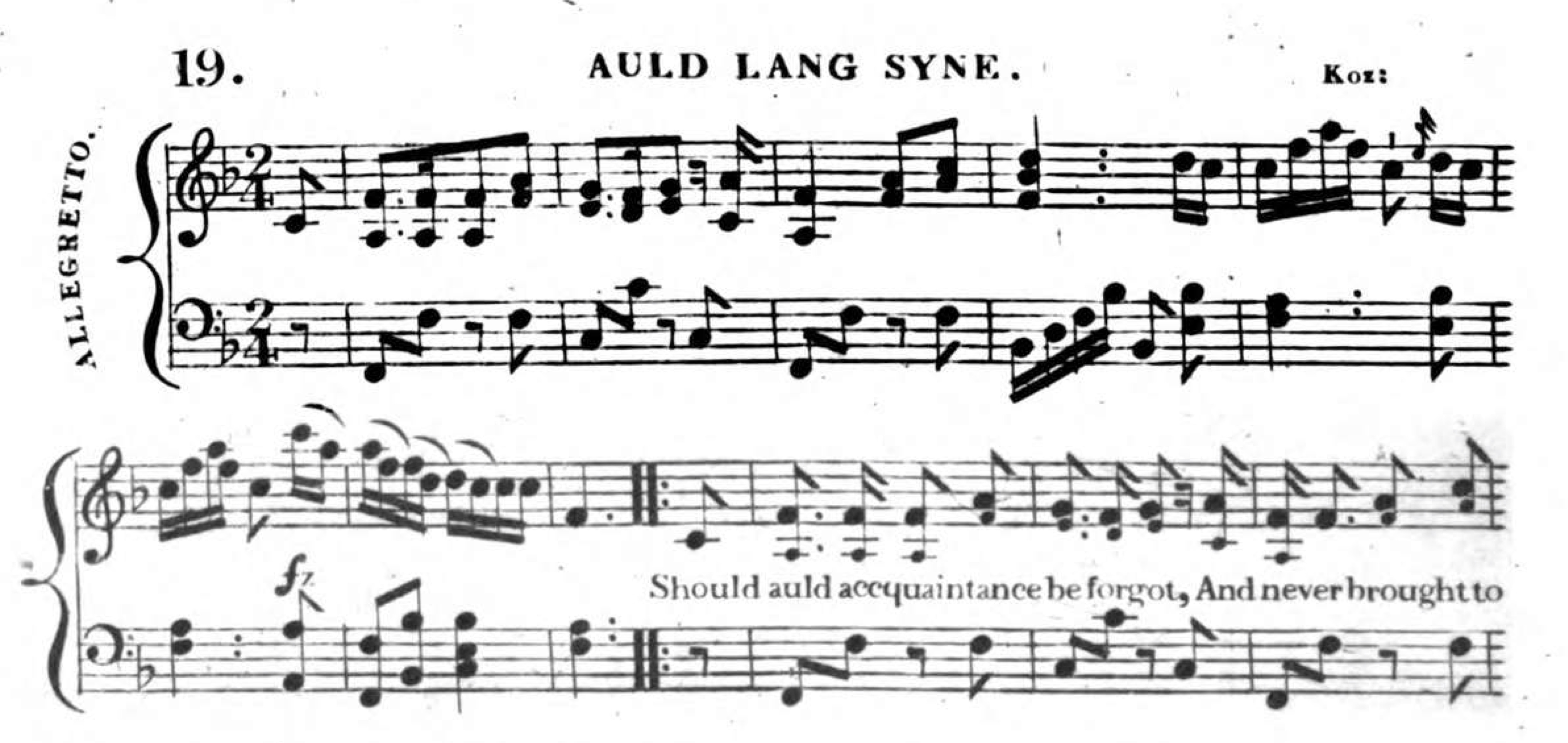

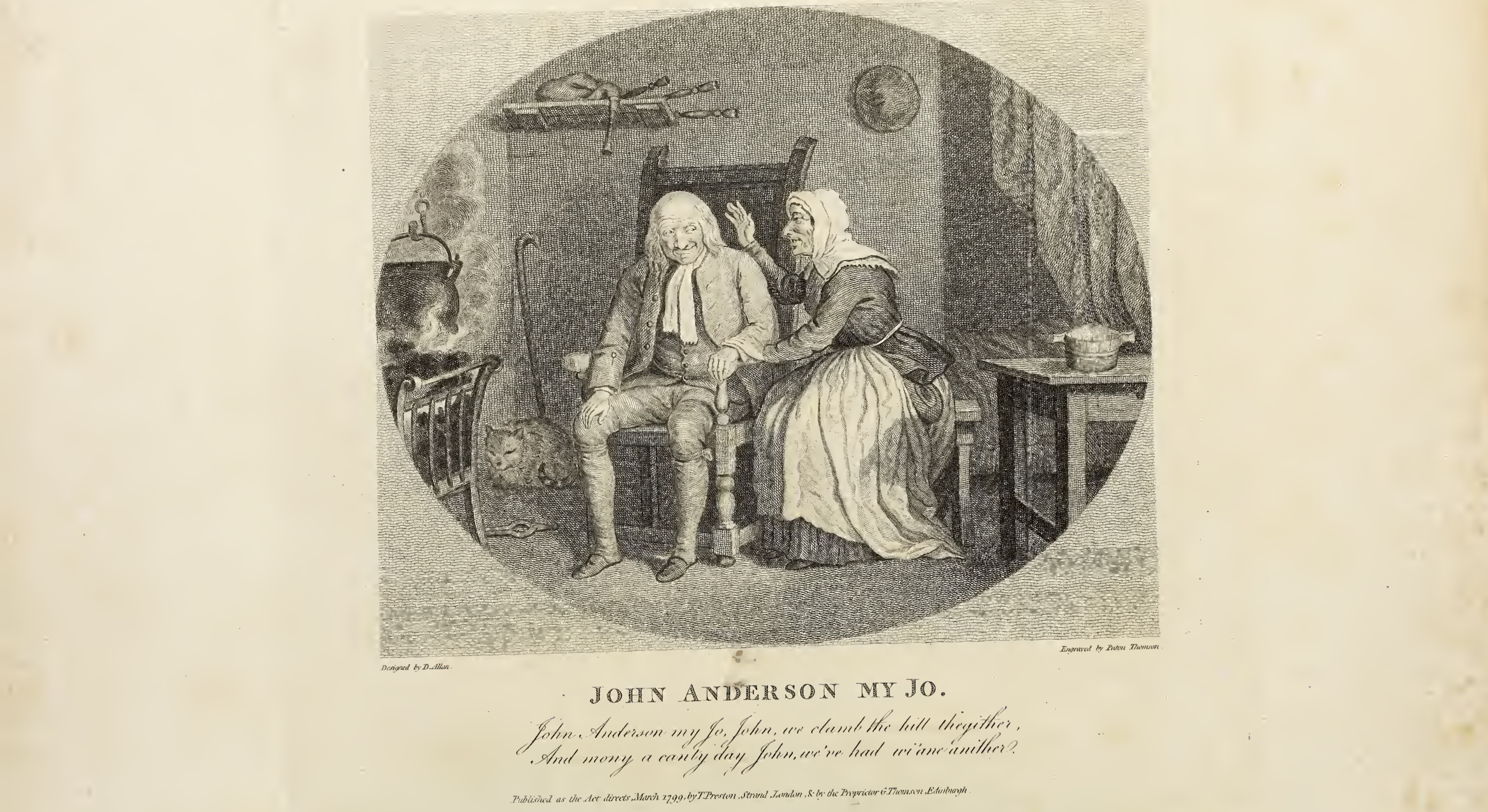

Insufferable nerd that I am, for the video I looked up the earliest published version of the tune by George Thomson from 1801. One interesting thing about the Thomson publication is that he hired some of the most famous composers of the time (none of them Scottish, or even English) to create the arrangements and accompaniments - including Haydn and Beethoven. In a way it’s hard to believe such successful musicians would contribute to a collection of folk songs from a far away land. On the other hand, composers often have a great appreciation for folk music, so maybe it’s no surprise.

I made some changes to the arrangement to make it work for cello and bassoon, but I tried to stick as closely as possible to the accompaniment by Leopold Koželuch. (Koželuch wrote some neat stuff - if you haven’t heard of him, try his keyboard sonatas, or his trios with keyboard, flute, and cello). It’s a nice arrangement, keeping close to folk style while adding what we might think of as ‘Classical’ touches. A lot of the arrangements in the collection are like this, and it’s definitely interesting to see what Haydn and Beethoven in particular did with the Scots songs. The Rare Fruits Council (best-named group in early music…) has a great recording of some of the Haydn if you want to get a taste.

Looking into the old edition, though, I learned a lot more than just some nuances of melody. I realized, for instance that I didn’t actually know any of the words of Auld Lang Syne after the first verse, not even the chorus! And I definitely had never heard the song in the original dialect. In case old acquaintance isn’t all you’ve forgot, here’s the entire Scots version as Robert Burns submitted it to the Scots Musical Museum in 1788:

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and auld lang syne?

Chorus:

For auld lang syne, my jo,

for auld lang syne,

we’ll tak’ a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

And surely ye’ll be your pint-stoup!

and surely I’ll be mine!

And we’ll tak’ a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

Chorus

We twa hae run about the braes,

and pou’d the gowans fine;

But we’ve wander’d mony a weary fit,

sin’ auld lang syne.

Chorus

We twa hae paidl’d in the burn,

frae morning sun till dine;

But seas between us braid hae roar’d

sin’ auld lang syne.

Chorus

And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere!

and gie’s a hand o’ thine!

And we’ll tak’ a right gude-willie waught,

for auld lang syne.

I’ll leave it to you to look up some of the unfamiliar words from Scots dialect, but I just want to point out what a difference it makes to hear the original Scots, as opposed to a more familiar modern English version. ‘Gowans’ is so much woodier than the tinny translation, ’daisies.’ Likewise ‘burn’ versus ‘stream.’ I won’t venture to tell you what the differences all add up to in terms of meaning. But as usual in translation, what we gain in readability, we lose in… well, something. Call it ‘authenticity,’ if that term doesn’t make you wince. I prefer ‘specificity’ but choose your own adventure. Character. Style.

It’d be tempting to go in for a nostalgic “good old days” take on the song. The old ways were great, and we’re living in a debased, degraded age that doesn’t appreciate the originals! But we ought to know better by now. No one should need convincing that the old ways were decidedly not always great. And as John Hodgman likes to put it, nostalgia is a toxic impulse, at best unproductive, at worst, poisonous. The past isn’t coming back, and trying to claw our way back to it isn’t helping anyone.

I think a better lesson comes from James Joyce, who said, “In the particular is contained the universal.” That’s what I hope groups like PBO are trying to do when we present old music. Not to recreate the past “the way it really was,” but rather to attempt to find the specificity, the particularity, the style in what came before, and to present that as a compelling alternative to the most general (if more understandable) contemporary version.

Maybe the past isn’t coming back. But we don’t have to forget it either. We can take a look back, learn from days gone by, give a hand and take a right good cup of kindness for auld lang syne.